Hi, I’m Harris and I work for the Freedom of the Press Foundation. I manage several Wagtail-powered sites there and if you’re interested in hearing more about that, please look up my talk from Wagtail Space US last year “Using Wagtail to Fight for Press Freedom.”

Today I want to talk to you about how to solve your problems by reading Wagtail’s code.

To start off, who here has read parts of the Wagtail code before? I want to see how much I’m preaching to the choir before we start.

Okay, some of you. Well, hopefully there will still be some interesting bits in this talk for you and for those of you who have never cracked open the codebase, hopefully today I can convince you to take a look inside.

So, how do we solve problems? I’m talking about when you first sit down to develop some new feature for your project and you think to yourself, “Wow, I really have no idea how to do this.” Where do you go first?

Hopefully, for most of us, the first stop is the docs. Wagtail’s docs are great and being constantly improved! There’s a shocking number of things built into Wagtail that I wouldn’t know about if I didn’t check through the docs before writing code.

But eventually you’re going to want to do something really off the beaten path that the documentation writers didn’t think to write about. And no matter how long you browse the docs for, you’re never going to be able to figure out how to do it by reading those alone.

So maybe you check out Wagtail Slack or StackOverflow. Wagtail has a really great and active community of developers who can help answer your questions. It’s a great way to find out if the problem you’re solving is actually something that’s been done before and if someone has a quick way for you to do it.

But you’re going to be limited to whoever is online and has free time and knowledge about your question. Maybe less obviously, though you yourself aren’t familiar with the code that you’re asking about, you’re counting on someone else to be. So even if you yourself haven’t read the code, you’re hoping that someone else has.

Here’s where we start getting a little deeper into how you figure things out for yourself. Maybe you just throw a bunch of stuff into a Python file and see what it spits out. You’re not reading the code, but you’re making some reasonable guesses about what it looks like and getting a sense of the shape of it from experimentation.

If you’re really good at this, maybe you even use PDB (or in this case IPDB, which I highly recommend) to do it. You can really get a feel for the interface of an object by poking around in a debugger, especially if, like IPDB, it sports a autocomplete that will list all of an object’s methods for you.

Before we move on, what other tools do you have for solving a problem that you’re not immediately sure how to approach? Is there anything I’ve missed? Maybe you hire someone who’s more knowledgeable than you about Wagtail to solve your problem.

[The audience suggested a couple things including using an IDE and looking at sample Wagtail projects like the Wagtail Bakery or the Torchbox website.]

But let’s say you exhaust those options and you’re still not sure what to do. All of the ways of solving problems so far that I’ve listed have limits. Say, your problem isn’t in the documentation. Maybe you’re on a timeline and you don’t have time to wait for someone on Wagtail Slack to get back to you and experimentation isn’t telling you much. Maybe you don’t have the time or money to hire someone else to solve this problem for you. I’m not saying these are bad ways to approach problems, of course—they’re often quick and they’ll probably usually work for you! But sooner or later you’re going to encounter a problem where you’re really stuck. What do you do next?

I want to argue, if you haven’t done it before, reading the code is easier than you expect it to be and it means that you will never be stuck.

I think we Wagtail devs are lucky that we code in a language that’s designed to be easy to read. You’ll sometimes hear Python developers say “the code is the documentation” and I think they’re wrong (please, please, write real documentation for your projects) but they’re not that wrong. And well-organized open-source projects like Django and Wagtail can actually be a pleasure to peruse.

Why should your read the code? Aside from the obvious answer that it might solve your problem, reading the code does a few other things:

When you read code, it makes you a better coder. You get a sense of how other people solve problems and in the case of a well-maintained established project like Wagtail, it can build your repertoire of best practices. It also means that while you’re coding you’ll be in the habit of thinking about the next person who needs to read your code.

When you read the code, you understand your tools better. You might come across things that help you understand why something in Wagtail works the way that it does or you might build knowledge for the next time you encounter a problem in the same arena.

When you read the code, you know whose fault it is. Sometimes you encounter a problem and you think to yourself “What am I doing wrong here” and then you’ll read the code and say “Ah! It’s not my fault. This is a bug!” And then you’ll report the bug on the Wagtail GitHub issue tracker and everyone’s lives will be better.

Finally, reading the code prepares you to contribute back. You’ll be familiar with Wagtail’s code already and it will seem less intimidating to add some of your own.

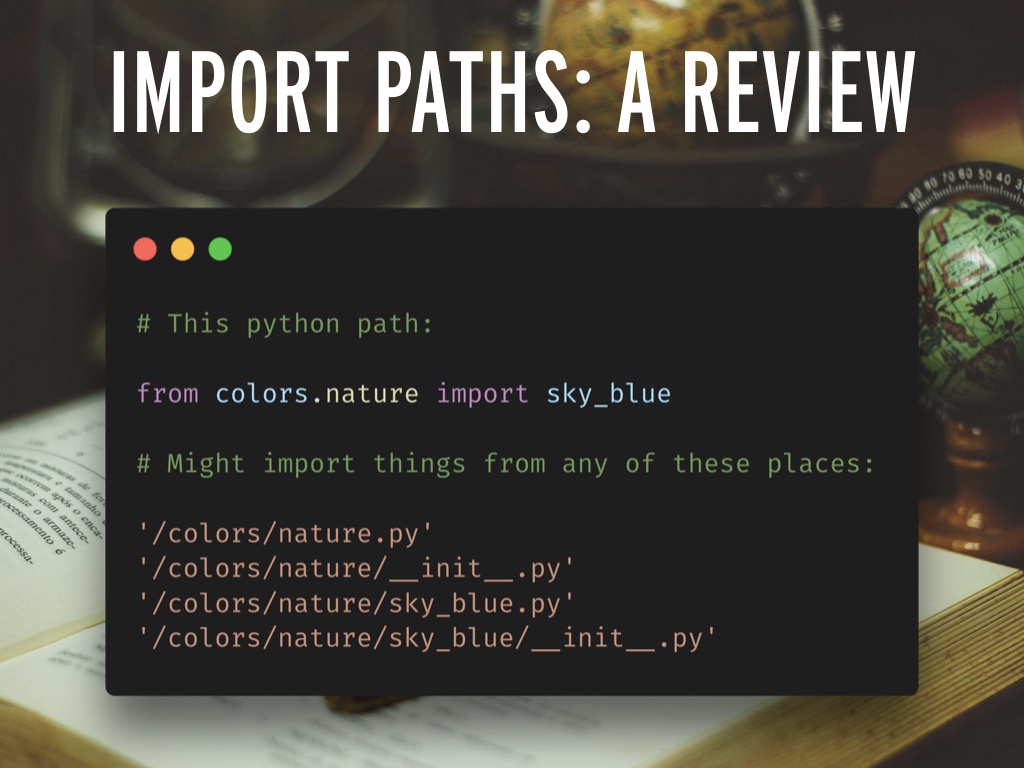

How should you get started reading the code? I’m going to take you through one example I encountered of solving a problem by reading the code, but before I do, I want to make sure we’re all on the same page by going through a quick review of how Python import paths work

A Python import path is basically a file path that directs Python to load code from another file. So in our example here, importing `sky_blue` from colors.nature might tell python to look for an object named `sky_blue` inside of the `colors/nature.py` file, or maybe inside of `colors/nature/__init__.py` if colors/nature is a directory, or it might tell it to import all of the objects inside a `sky_blue.py` file or inside of a `sky_blue/__init__.py` file if `sky_blue` is also a directory.

In general it will looks for these files either inside the directory of the script that’s running (in most cases for us, that will be the directory that `manage.py` is in) or in the packages that you’ve installed using pip or pipenv or whatever.

That’s a bit of an oversimplification, but it should be enough to tell you where you’re looking for the relevant code to read and why you can import from `home.models` and have it come from your code, but import `wagtail.core.models` and have it come from the version of Wagtail you installed.

If you want to actually see all the folders on your hard drive where Python looks for files to import, you can run this snippet of code. Note that you’ll get something slightly different running it from shell like this than if you run it inside of a file.

Anyway, enough about Python imports. Let’s get to my problem.

Wagtail has an excellent form builder. If you’ve never used it, this form builder basically lets the developer create a page type that content editors can use to create forms on the website—basically a simplified version of something like Google forms. And in particular, Wagtail forms offer the ability to create form pages that automatically send emails to a specific recipient when they get a submission, like your support team or admin or web developer. We use these all over FPF’s websites

From simple contact forms

To user surveys

But wait a second. Wagtail forms let content editors specify a subject line for all form submissions, but we found that a little limiting. In particular, these form emails get automatically ingested by our support system and we wanted ticket names that were more informative than “Form Submission.” We wanted site visitors to be able to provide their own subject as part of filling out the form and have that become the subject line of the email. So there’s the problem we wanted to solve. How should we go about it?

Let’s start by trying some of the approaches we talked about before.

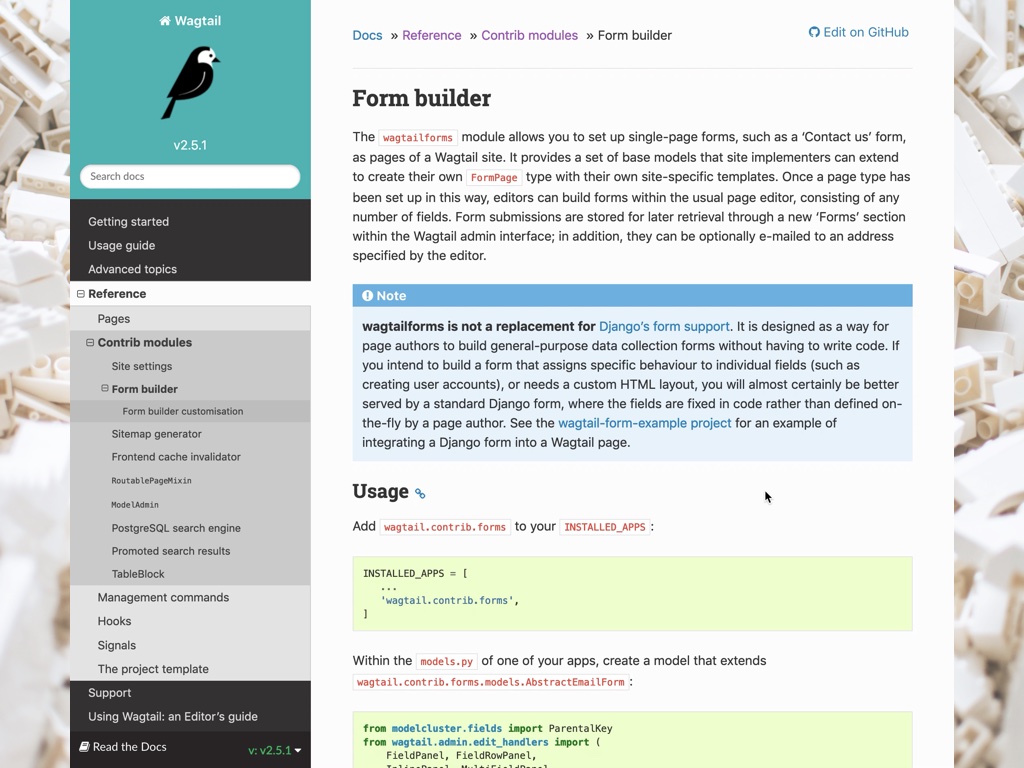

First, reading through the docs. It looks like using the form builder is pretty well documented, but the docs are fairly brief and I don’t see anything here that’s relevant to my specific problem. So that’s a no go.

Okay, let’s try seeking out some volunteer members of the Wagtail community to provide us with support. I could go post in Wagtail Slack #support channel right now or add a question to StackOverflow, but instead, since I have all of you in front of me, I want to do this as an experiment. Sort of a dangerous experiment for me to be doing in a room that has so many Wagtail core devs, but can anyone in here tell me how to solve my problem?

(If someone responds with the correct answer: Yes, you’re right. But let’s imagine {{ PERSON }} wasn’t available to answer my question when I asked it in Slack. I mean, they’re a pretty busy person and can’t always be around.)

[The audience provided a few guesses, but no one knew immediately how to do it.]

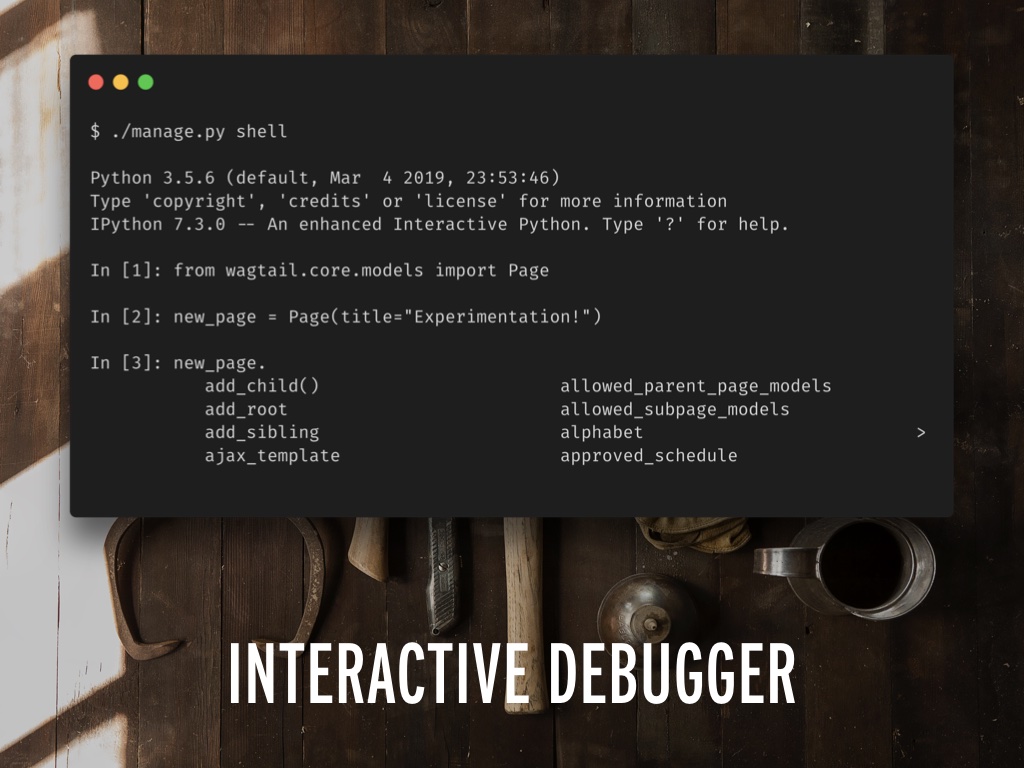

Okay, let’s try figuring this out through experimentation. I’m a big fan of playing around in interactive shells so I’m just going to pull up a Django shell to experiment in.

I import our email contact form model, instantiate a page so I have an object to play around with, and then use iPDB’s tab completion to see what methods and attributes are available and wow that’s a lot of methods. I’m a little bit at a loss of where to start with all this.

Let’s try reading the code.

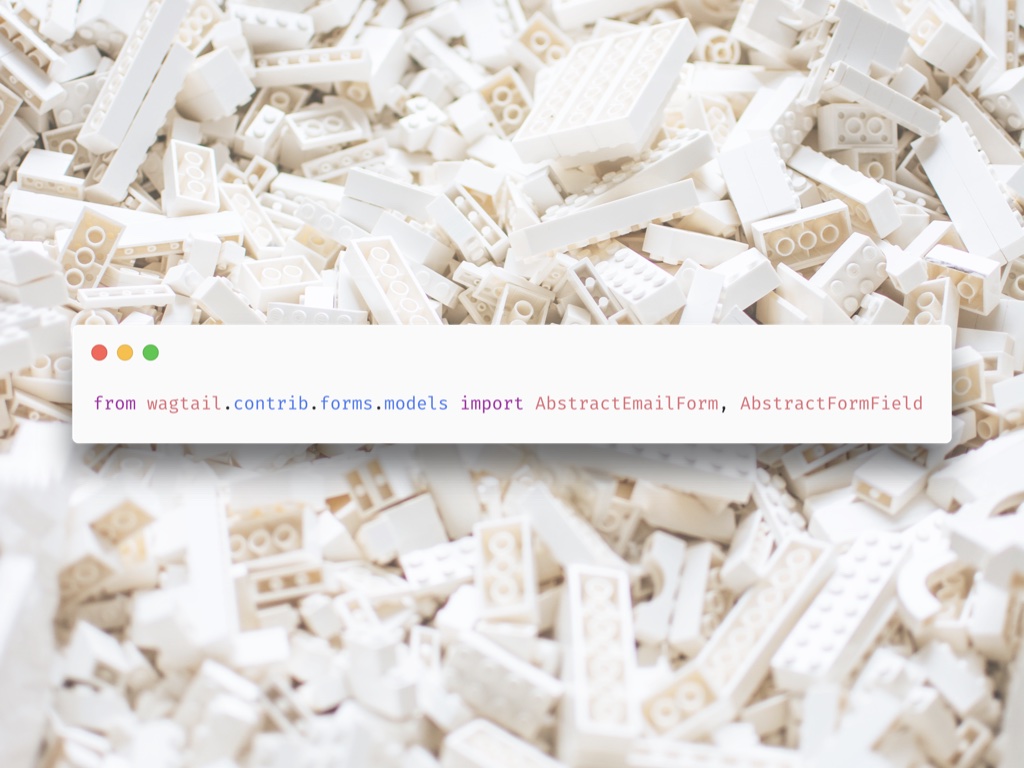

First, let’s look at our own code that we’re working with. We can start figuring out where to look based on this line straight from the docs.

You can look for this file on your filesystem if you want, but I usually find it easier to just browse Wagtail’s code on GitHub for it. Just make sure you’re looking at the same Wagtail version you’re using.

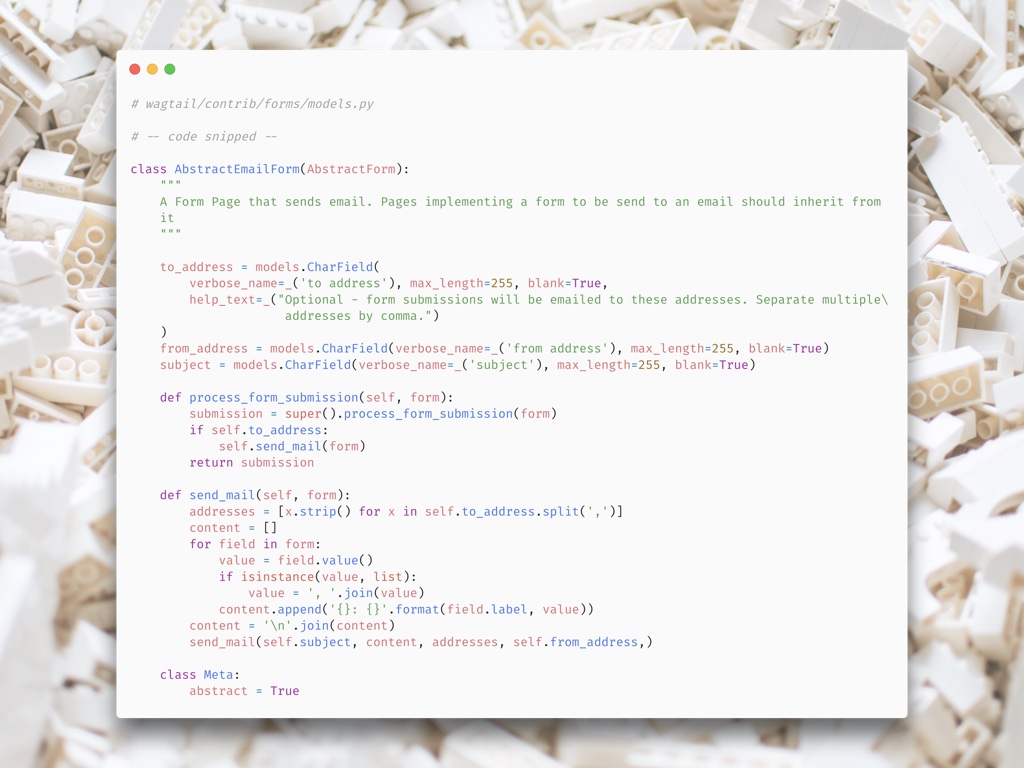

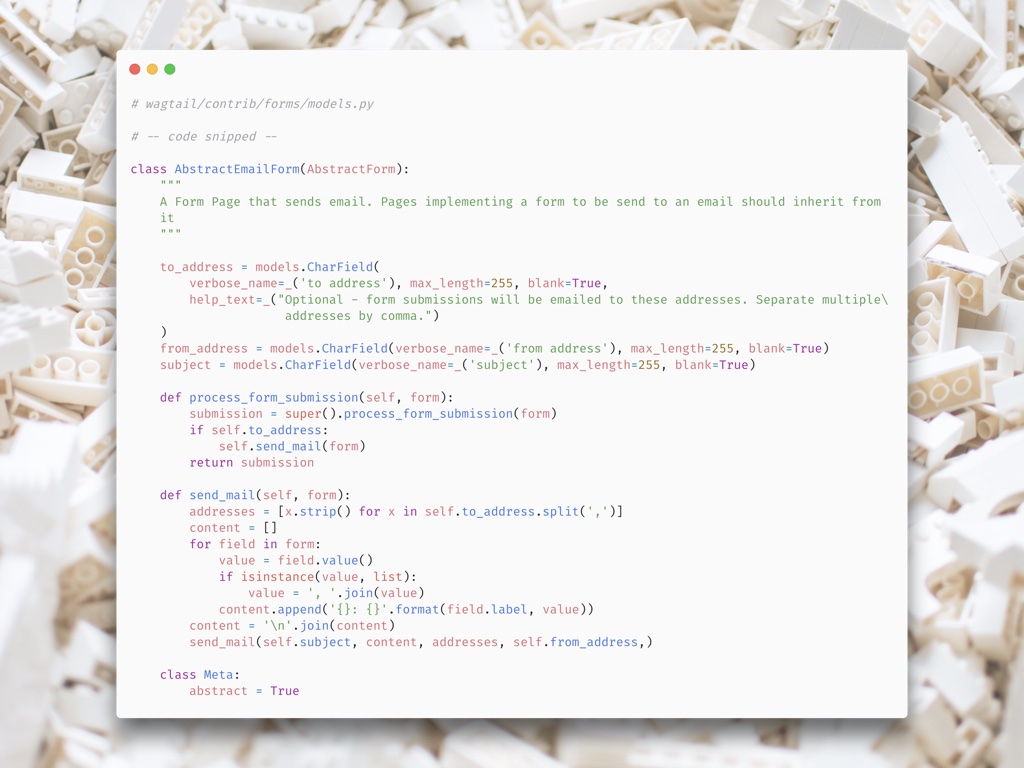

This looks very promising. I can see this `send_mail` method that I can make a pretty good educated guess is where Wagtail actually sends the form submission email. If I want to be totally confident, I can spool around this file a bit. I see that `send_mail` is called from `process_form_submission` up above in the same class. If I scroll up just a little in the same file I can find the superclass `AbstractForm` that the `AbstractEmailForm` inherits from.

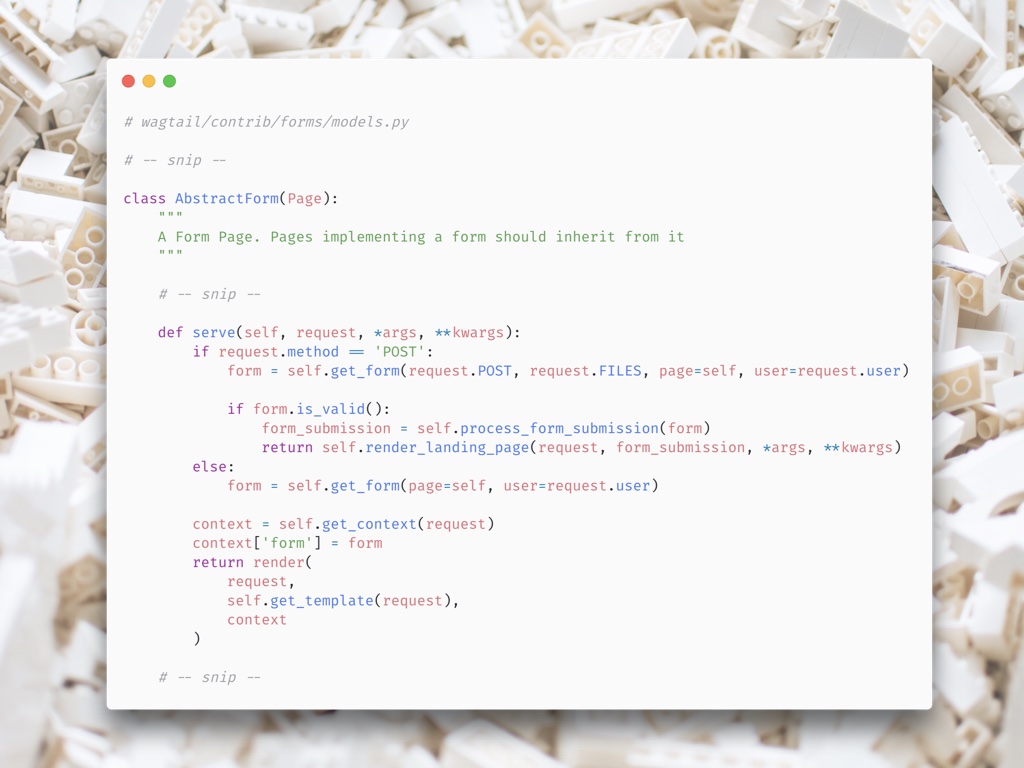

I find that superclass has this serve method, which I happen to know is the method Wagtail pages use for handling requests. If I read through this method I can see that when it encounters a POST request—a form submission—it checks if the form is valid and cals the `process_form_submission` method. Which confirms that `send_email` does in fact get called when a form is submitted.

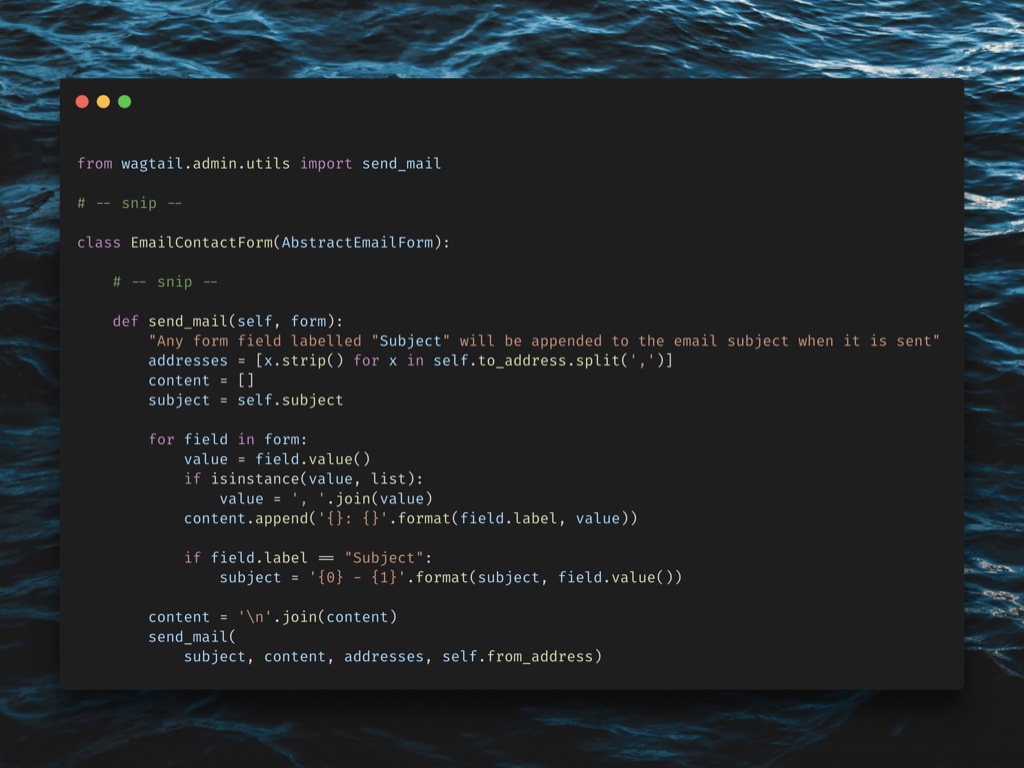

So returning now to the `AbstractEmailForm`, we can read through this `send_mail` method and understand what it’s doing.

- It reads off the `to_addresses` field, splits them by commas into and strips whitespace off of them using a list comprehension. Seems pretty predictable

- This `for` block here looks like it’s creating an array of strings of the form `key: value` for every field on the form and then putting them together with line breaks. That makes sense.

- And here’s the critical line, where it send the email using that `content` as the email content and the `subject` from the page field. We want that subject to come from one of the form fields instead.

Now that we understand the code, we can start coming up with a solution.

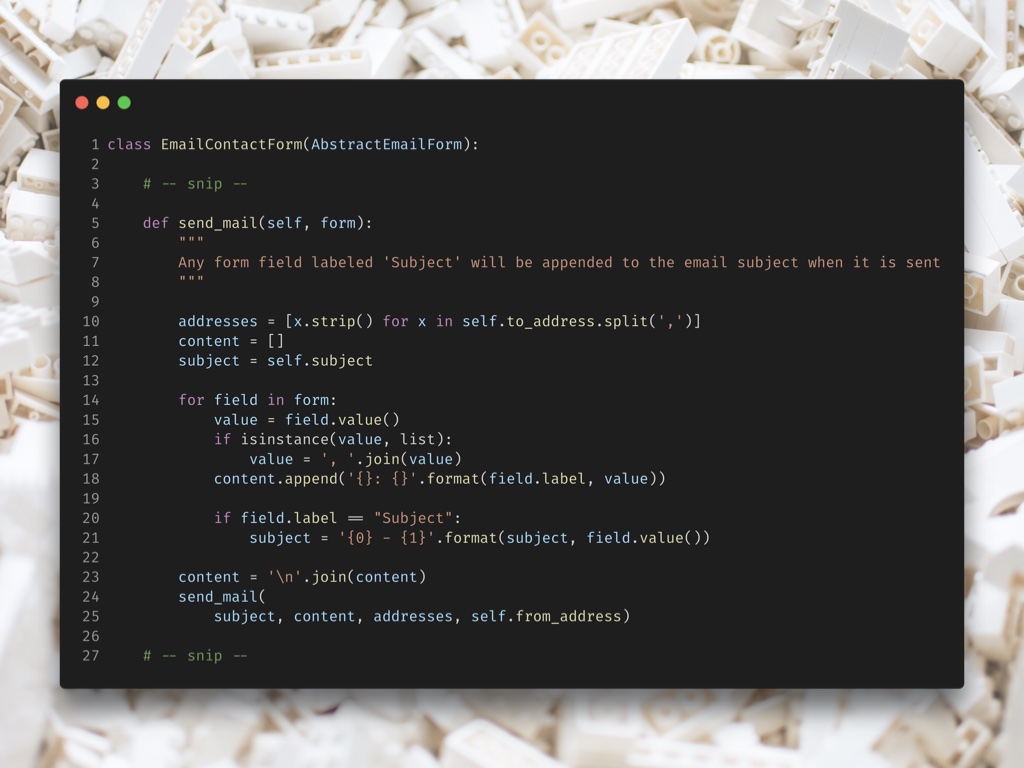

There might be any number of ways of solving this problem now that we understand what’s going on under the hood, but the one we chose was to override the `send_mail` method. We basically copied the method over and then, as you can see on lines 12, 20, 21, and 25, added some logic for dealing with the subject.

Basically this logic checks if each field has the label “Subject” (this field would be defined by a content editor from the admin). If such a field exists, it interpolates the value of that form field into a new subject line. If no such field exists, it uses the editor provided subject line as usual.

That’s an example of a solution that could never be arrived at without reading the code. But reading the code isn’t just about finding undocumented methods. For example let’s say not only do we want to have a dynamic subject line, but we want to really spruce up the emails we receive into fancy HTML emails with like colors and a table and everything! Let’s look at our form page code again.

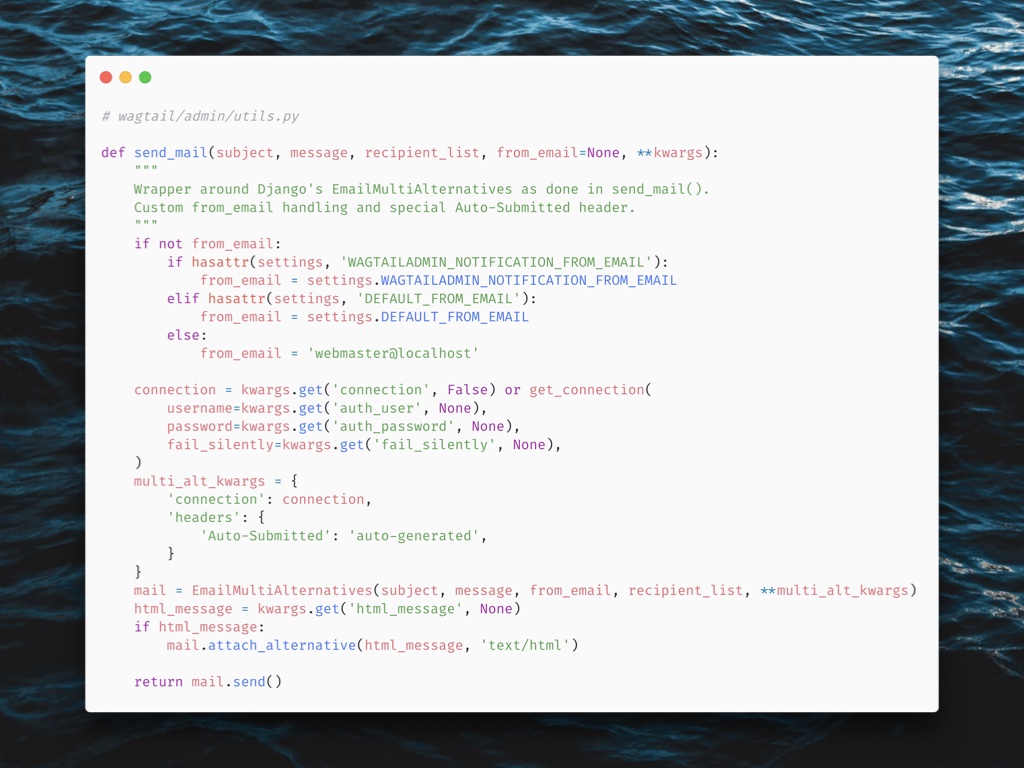

Notice we’re using a `send_mail` function (different from the `send_mail` method on the form page) that comes from Wagtail. We copied that over as is from the `AbstractEmailForm` method. If we want to generate an HTML email to send, that seems like a good first place to look. Let’s see what that function actually looks like.

Now, before we get to answering our question of how to add an HTML message, I just want to say, there’s a whole lot of interesting stuff going on in this function that I would never know about if I hadn’t tried to read it.

First of all, if we look at this top block here, we can see that if we weren’t providing a `from_email`, it would default to one of these three email addresses: the setting for the wagtail admin notification emails, or the setting for default from email as a fallback, or just `webmaster@localhost` as a final hardcoded fallback. None of that’s necessarily useful information to me right now, but if someday I start seeing emails coming through Wagtail from `webmaster@localhost` mysteriously, I’ll now have a pretty good idea where to look for more info.

Secondly, it looks like if we want to we could use a custom email connection if we wanted to. I don’t need to do that right now, but it’s nice to know.

Finally, looking way down at the bottom few lines, it looks like we can add an HTML message just by providing an `html_message` kwarg. I’m not going to walk through the process of writing that feature with you all now, but you can see how you would start to do that and you can see how reading the code made that knowledge possible.

I’m hoping by now, if you’ve never done it before, I’ve made the prospect of reading the code to solve your problems a little less daunting and I’ve shown you how it can make solutions to difficult problems approachable.

Whenever you’re working on a problem and you run into a brick wall, I recommend reading the code that’s relevant to whatever you’re working on. Even if you’re not sure exactly what you’re looking for, it can give you a better perspective on the library you’re working with.

If you still feel like you’re struggling, that’s OK. Especially with code bases that are more complicated than Wagtail, reading and understanding code takes time. It’s also a skill that can be practiced. The more you do it, the faster you’ll get at surfacing the stuff that’s relevant to you and understanding it. The more you do it the better you’ll understand your tools, the better your own code with be, and the more prepared you’ll be to give back to the open source community.